Sumacs are shrubs or small trees that often form colonies from their creeping, branched roots. The foliage usually turns brilliant red, reddish orange, or purplish red in early autumn.

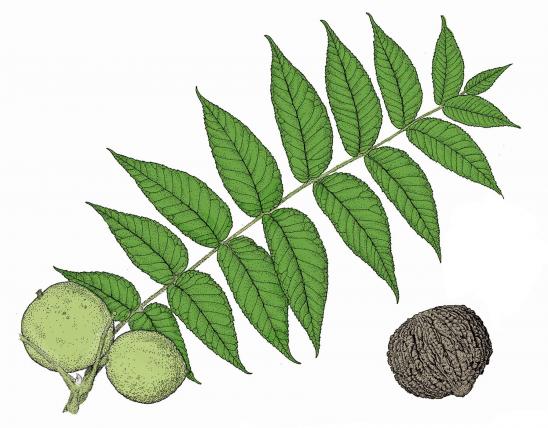

The leaves are feather-compound, with 3 to 25 leaflets, depending on the species. The leaflets of many species are often scalloped or toothed. Sumacs are often finely hairy.

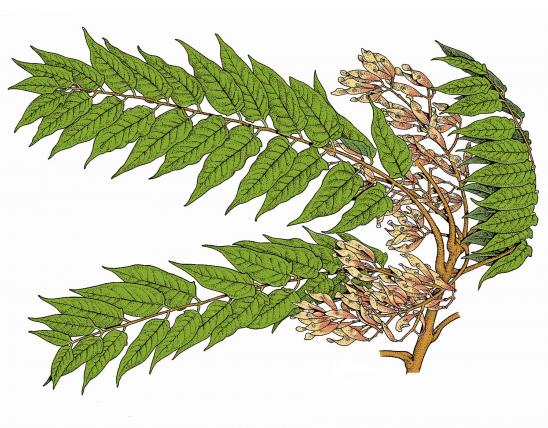

The flowers are in dense clusters that develop at the stem tips. The 5 petals are usually pale green or yellowish. The male (staminate) and female (pistillate) flowers occur on separate plants. The 5 sepals usually persist on the developing fruits.

The fruits are round and berrylike (often flattened), red or reddish, and noticeably hairy with red hairs. If you press on the fruit, the outer layer and fleshy or waxy middle layer easily separate from the smooth stone within.

Missouri has 4 species of sumacs:

- Fragrant (aromatic) sumac (R. aromatica) is never a small tree, so it is typically smaller than our other sumacs. It looks a lot like poison ivy, but this pleasant, nontoxic plant is easily told from its "evil cousin." Note the middle leaflet of its "leaves of three": On fragrant sumac, there is no (or at most a very short) leaf stalk on that middle leaflet. Also, fragrant sumac has hairy, reddish fruits (not waxy whitish ones), and it never crawls up trees as a vine.

- Winged (dwarf, or shining) sumac (R. copallinum) is most common south of the Missouri River. It is a thicket-forming shrub or small tree with a rounded top. The “wings” in the name refer to the narrow, flattened leafy structures running along the central stems of the compound leaves. The upper surface of the leaflets is shiny and lower surface felty-hairy.

- Smooth sumac (R. glabra) is scattered statewide. It is a thicket-forming shrub or small tree with a spreading crown. Unlike winged sumac, it lacks flattened leafy “wings” along the central stems of the compound leaves. The branches and undersides of leaves lack hairs and are glabrous with a whitish, waxy coating. The red hairs on the fruits are dense, tiny, and short.

- Staghorn sumac (R. typhina) is not native to Missouri, but it occurs in introduced populations in Greene County, in the St. Louis region, and possibly elsewhere. It is native to states farther east and north of Missouri. It is usually taller than our other sumacs, typically growing 15 to 25 feet high. It has densely hairy branches, and the fruits are densely covered with slender, straight, red hairs that are nearly ⅛ inch long. The feather-compound leaves are sometimes doubly compound. Like smooth sumac, the leaf stalks lack wings. The hairiness of the fruits and stems resembles the velvet of deer antlers; hence the name.

Similar species: Poison oak and poison ivy are in the same family but in a different genus (Toxicodendron). In the past, however, they have been placed with sumacs in genus Rhus. Note that poison ivy (T. radicans) and eastern poison oak (T. pubescens) both have 3-parted compound leaves (never more than 3 leaflets); loose (not dense) flower clusters that arise from the leaf axils (and not just at the top of the stalk); and fruits that are whitish or yellowish (not red or reddish) and are hairless or (at most) inconspicuously hairy.

There is a plant called “poison sumac,” but although some people have used that name for Missouri species, it technically belongs to a plant that does not occur in Missouri. True poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) has feather-compound leaves with 7–13 leaflets whose margins are entire (lack teeth or lobes); its berries are green, ripen to white, and droop downward; it occurs in swamps and bogs in states beyond our borders, to the east and north.

Another lookalike is the invasive tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima). The leaflets are notched at the base, and the seeds are in clusters with flattened, twisted, light brown wings.

Golden rain tree (Koelreuteria paniculata) is another lookalike invasive plant. Its leaflets are irregularly lobed and deeply toothed; emerging leaves are bronze, pinkish, or purplish. In autumn, the leaves turn dull yellow (not red). The fruits are inflated, 3-parted capsules that give the plant its common name “Chinese lantern tree.”

Height: Fragrant sumac, our smallest species, ranges from 1½ to 5 feet; staghorn sumac may reach more than 20 feet, and smooth and winged sumac often reach 15 feet.

Statewide. Different species have different ranges and slightly different habitats.

Habitat and Conservation

Fragrant sumac is found in glades, bluff tops, savannas, openings in upland forests, old fields, railroads and roadsides. Winged sumac occurs in glades, upland prairies, savannas, openings of upland forests, and open disturbed areas. Smooth sumac occurs in open woods, brushy areas along roadsides, and fencerows. In Missouri, staghorn sumac (introduced from states to our north and east) occurs along railroads, highways, and other open, disturbed areas.

Status

Three of our sumac species are native. Staghorn sumac has been introduced from regions to our east and north, but although it may persist in locations, it is not considered invasive.

Human Connections

Historically, sumac species were used by Native Americans for a variety of medicinal purposes — to control vomiting and fever, treat scurvy, and as a poultice for skin ailments.

The tart fruits have been chewed as a breath freshener, and old-timers and wild-edibles enthusiasts make sumac tea from the fruits. The beverage is somewhat lemony, and many people add honey or other sweeteners to make a kind of wild lemonade. (There are many tips online.) Be advised that sumac berries may contain trace amounts of the same chemicals that are abundant in poison ivy, so a very small percentage of people who are highly sensitive to poison ivy may develop a strong allergic reaction to drinking sumac tea.

As summer draws to a close, Missouri’s roadsides, fields, and open woodlands begin to show the colors of autumn. Sumacs are a big part of our early fall color season, delighting travelers with their clusters of bright red foliage. Usually, sumacs drop their leaves before the climax of fall color in mid to late October.

You may have eaten Mediterranean food with a sour, maroon-colored power sprinkled over the top. That is za’atar (zatar), an ancient seasoning blend made with the dried, ground berries of Sicilian or elm-leaved sumac (Rhus coriaria), plus certain varieties of thyme, oregano, savory, toasted sesame seeds, and/or other ingredients.

In the Old World, sumac foliage was used to tan leather. The famously soft Morocco leather was traditionally tanned with sumac.

Sumacs are in the same family as poison ivy, but this is also the same family as several economically important fruits and nuts, including pistachio, mango, and cashew. To some degree and in at least certain parts of the plants, all contain urushiols — the same chemicals that cause dermatitis from poison ivy. One reason why cashews are so expensive is that the process of preparing them for sale and export releases a caustic resin that can cause skin to blister.

Some sumacs, especially fragrant and winged sumac, have grown in popularity as landscaping shrubs. One big benefit is their brilliant fall color. Their thicket-forming growth make them good for parking lot and highway-median plantings. They generally need a lot of space where they can be allowed to spread and form colonies. Smooth sumac is less widely planted, because it can spread aggressively from its tough rootstocks and can be tough to eradicate. Fragrant sumac can make a good foundation planting or a good screen during the growing season; there are a selection of varieties and cultivars available.

The word “sumac” has come to our language, via French and Latin, from a similar-sounding ancient Syrian/Aramaic word meaning “red.”

Ecosystem Connections

Many types of birds eat sumac fruits, and deer, rabbits, and other animals browse the berries, stems, and foliage. To survive during severe winters, rabbits may eat the bark of fragrant sumac.

The colonies of these shrubby plants provide important cover for many kinds of animals.

Sumacs are energetic colonizers of landscapes, so they can stabilize raw soil.

Smooth and winged sumacs, being tough spreaders, can invade prairies; the presence of these and other woody plants is a sign of a degraded prairie in need of prescribed burning or other natural disturbance.

A variety of bees, flies, and other insects visit the flowers for nectar, pollen, or both.

Certain types of carpenter bees hollow out the soft pith at the center of sumac stems and use the tunnels for larval nests.

Sumac leaves are an important food for the caterpillars of the red-banded hairstreak butterfly, the spotted datana moth, and the regal or royal walnut moth. The larvae of nine additional butterflies and moths have been recorded feeding on sumacs.

The sumac gall aphid (Melaphis rhois) is one of the few aphid species to form galls, and sumacs are required host plants. These aphids have a complicated life cycle; the winged females, at the end of summer, require mosses as alternate host plants. Look for their unevenly rounded, green to reddish, pouchlike galls that develop from the leaf stems of sumac. These curious insects do not cause meaningful harm to the host plant.

Several other insects feed on sumacs, including the sumac stem borer (Oberea ocellata) and the sumac flea beetle (Blepharida rhois).