The Rocky Mountain toad (our subspecies of Woodhouse's toad) is Missouri's largest toad. It is a medium-sized toad with a number of irregular dark brown or black spots on its back, with 1–6 “warts” inside each spot. The general color may be green, greenish gray, gray, tannish gray, or brown. The belly is white and usually unspotted, but some individuals may have a single breast spot. A tan or white stripe usually runs down the back. The large, wartlike parotoid gland behind each eye is oblong and is connected to the prominent bony cranial crest above each eye. The male's call is a short, nasal “w-a-a-ah,” lasting from 1 to 2½ seconds, similar to the call of the Fowler’s toad, but with a lower pitch.

Similar species: Fowler’s toad (Anaxyrus fowleri) used to be considered another subspecies of Woodhouse’s toad (Anaxyrus woodhousii), but genetic analysis and breeding call studies revealed that is should be considered a fully separate species.

In areas where their ranges overlap, the Rocky Mountain toad probably hybridizes with Fowler’s toad and the American toad (A. americanus). Where this happens, intermediate characteristics will occur, making identifications tricky.

Members of the true toad family (Bufonidae) live nearly worldwide, except for New Zealand, Australia, Madagascar, and the polar regions. The family comprises 47 genera with more than 590 species. In the United States, there are 19 species of true toads, and all are members of the genus Anaxyrus. In Missouri, there are 4 species of true toads, with 1 additional subspecies.

True toads have dry skin compared to frogs. They have no teeth, lack extensive webbing on the hind feet, and have large, wartlike parotoid glands behind their eyes. Numerous “warts” over most of their bodies produce toxic skin secretions that are irritating to a predator’s mucous membranes.

Adult length (snout to vent): 2½ to 4 inches; occasionally to 5 inches. Females are larger than males.

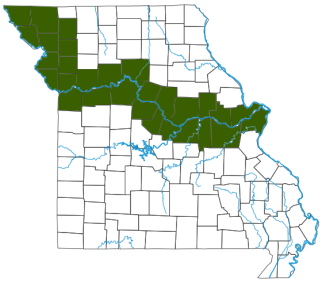

In Missouri, this toad occurs primarily within the Missouri River floodplain, from the central to the far northwestern parts of the state. The range may extend as far east as St. Charles County and western St. Louis County. It has a wide range in North America.

Habitat and Conservation

This species prefers sandy lowlands, particularly river bottoms, and open, dry areas adjacent to marshes, as well as around homes in urban and suburban areas. The Rocky Mountain toad is the most abundant toad found in the sandy soils within the Missouri River floodplain. They can be observed in large numbers on roads after warm spring or summer rains.

Like other toads, they hide in burrows by day and become active at night as they forage. All of Missouri’s species of true toads are primarily nocturnal.

Food

Hunts at night for a variety of insects and other invertebrate prey.

Toads are well-known for their consumption of large numbers of insects. During summer nights, toads often catch and eat insects as they fall to the ground under outdoor lights.

Status

The Rocky Mountain toad is the most abundant toad found in the sandy soils within the Missouri River floodplain.

Taxonomy: With recent taxonomic changes, the Woodhouse’s toad group (Anaxyrus woodhousii) currently has two recognized subspecies: the southwestern Woodhouse’s toad (A. woodhousii australis) (which does not occur in Missouri) and the Rocky Mountain toad (A. woodhousii woodhousii). The common name "Rocky Mountain toad" replaced the formerly recognized common name "Woodhouse’s toad." However, it is likely that additional taxonomic changes might be warranted between these two subspecies as more information becomes available.

Life Cycle

Although individuals can become active in late March, breeding does not begin until late April or early May; it usually peaks in mid-May to early June and continues into July. Males congregate along the edges of river sloughs, shallow ditches, ponds, and flooded fields. Like other species of toads, a female of this species typically lays several thousand eggs. These hatch in about a week or less. The black tadpoles begin to change into toadlets by late June or mid-July. The time they spend as tadpoles varies with water temperature. The young toads mature very rapidly, reaching maturity during the first year after metamorphosis for males and second year for females.

Human Connections

Rocky Mountain toads are primarily found within agricultural areas of the Missouri River floodplain. They can sometimes eat up to two-thirds of their own weight within a single night. Because of their ability to consume large numbers of agricultural insect pests, they are considered economically important.

As an insectivore that lives along sandy river bottoms, this species is a friend to canoeists, fishers, and others who like to be near water but not be pestered by various insects. The distinctive calls add to the symphony of an outdoor evening on the river.

Contrary to superstition, toads do not cause warts on humans.

The species name, woodhousii, was created in honor of the physician and naturalist Samuel W. Woodhouse (1821–1904), who was part of the Sitgreaves Expedition of the American Southwest. Woodhouse also has a scrub jay named in his honor. He had collected both species on his western expeditions. He himself honored another naturalist, John Cassin, by naming the Cassin's sparrow after him.

Ecosystem Connections

This species provides food for several species of aquatic snakes, as well as other predators. Snakes that eat Rocky Mountain toads include the northern watersnake, hog-nosed snakes, gartersnakes, and other native watersnakes.

As a hunter itself, the Rocky Mountain toad checks the populations of many insect species.