Bloodroot is a stemless perennial wildflower with a fleshy, horizontal, fingerlike tuber with reddish-orange juice. The tuber sends up a flower stalk wrapped by a single palmate, deeply scalloped, grayish-green basal leaf. The leaf unfurls when the solitary flower blooms. After the flower fades, the leaves continue growing (to 8 inches wide) until midsummer, when the plant goes dormant: the leaf turns yellow and withers away, and the plant will bloom next spring.

The flowers open before or just as the leaves start to unfurl. As the flower opens, 2 sepals fall off, and 8–16 white petals of uneven size and length open into a horizontal position, forming a flower that grows to 1¼ inch across, with many yellow stamens. Because petals are of uneven length, one often finds “square” flowers. Each flower lasts only one or two days. Blooms March–April.

Fruits are about 1 inch long, borne upright, smooth, often with a thin whitish waxy coating. On maturity these split open lengthwise from the base into 2 parts.

Height: to about 9 inches.

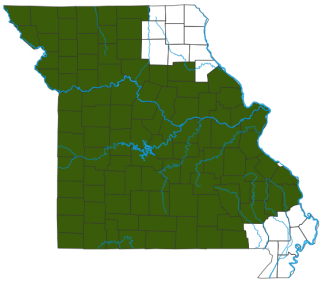

Scattered in the Ozarks and Ozark border; uncommon elsewhere in the state.

Habitat and Conservation

Occurs in bottomland forests, rich upland forests and woodlands, banks of streams and rivers, and bases and ledges of bluffs.

Status

Native Missouri wildflower.

Human Connections

Bloodroot is an attractive wildflower when grown in shade and woodland gardens, but it flowers early and for only a relatively brief time, dying back and going dormant soon after the fruits mature. The leaves are unusual and attractive, but they turn yellow and wither relatively soon, too. If you are interested in native wildflower gardening, make sure you purchase plants grown by reputable nurseries that propagate plants without harming wild populations.

In the past, Native Americans used the sap for dyes, and the rootstock has been used medicinally for its antiseptic and emetic properties. The sap can irritate the skin and has been used to treat warts and skin cancers.

More recently, a toxic alkaloid called sanguinarine (first extracted and described from Sanguinaria canadensis) has been used commercially as an ingredient in some toothpastes and mouthwashes, but in 2016 these were pulled from the market in the United States. The chemical has also been advertised as a treatment for cancer. This use has been controversial, as some researchers point out that such alkaloids may be carcinogenic. The US Food and Drug Administration has cautioned against using it, at least because it has no proven efficacy. Also, large-scale harvesting of bloodroot might eventually prove detrimental to the species.

Ecosystem Connections

Even humble plants that are dormant most of the year contribute to the complexity of the ecosystem, binding the soil with their rootstocks and providing pollen during their blooming time. The main pollinators of bloodroot are bees and flies. Native andrenid bees are the most efficient pollinators of this species. Bloodroot does not produce nectar, though many insects visit the flowers looking for it.

Mammals rarely eat bloodroot leaves or roots because of the bitter toxins.

Bloodroot is the only member of its genus.

Bloodroot is one of several kinds of spring wildflowers whose seeds have white, oily appendages called elaiosomes and are distributed by ants. The ants collect and carry the seeds to their nests, eat away the nutritious portion of the seeds, then discard the still-viable portion of the seeds to the “garbage” chamber of their nests, which is a perfect, protected place for the young plants to sprout and thrive. Violets, dogtooth violets, and Dutchman’s breeches are other plants with elaiosomes.

Like many other early spring woodland wildflowers, bloodroot is an ephemeral, appearing for only a short time and then going dormant for the rest of the year. Their life-cycle strategy is to bloom and make seeds, to gather solar energy and convert it to sugars with the leaves, and to store those nutrients in the rootstocks, all before the trees leaf out overhead and cast them in shade. This is the same basic strategy of tulips and daffodils.