The shells of zebra mussels are thin, elongated triangular, and inflated (not flat), with a prominent, angled ridge. The exterior is variable but typically has alternating light and dark bands. A concavity about midway in the shell allows the animal inside to secrete byssal (holdfast) threads, permitting the mussel to attach itself to almost any solid substrate. In areas infested with zebra mussels, they often clump together, covering rock, metal, rubber, wood, docks, boat hulls, native mussels, crayfish, and even aquatic plants.

Similar species: The quagga mussel (D. bugensis), is another nonnative invasive species. It is shaped and striped something like the zebra mussel, but it is more rounded and less angular and is usually paler near the hinge. It is currently causing problems in the Great Lakes and is starting to be seen in Missouri. Always Clean, Drain, and Dry boats and other gear that is used in water, and dispose of unused bait in the trash!

Adult length: ¼–1 inch.

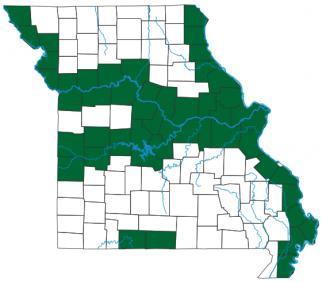

The range is spreading. Present in several Missouri reservoirs, including Lake of the Ozarks, Bull Shoals Lake, Lake Taneycomo, Lake Lotawana, and Smithville Lake. Also in several rivers, including the Osage (below Bagnell Dam) and the Missouri, Mississippi, and lower Meramec.

Habitat and Conservation

Native to the Caspian Sea region of Asia, these mollusks were accidentally introduced to North America in 1986 from ballast water of an international ship. They have tremendous reproductive capabilities and have a huge negative impact on the waters they infest. They starve and suffocate native mussels by attaching to their shells and the surrounding habitat in large numbers, caused severe declines of native freshwater mussel species in many areas. They have spread rapidly throughout the Great Lakes, the Mississippi, Arkansas, Ohio, Tennessee, and Cumberland rivers. No one has found a way to stop their spread, so the only thing to do is take steps not to spread them any further.

Food

Zebra mussels filter plankton from water. Each mussel can filter about a quart of water per day. But not all of what they remove is eaten. What they don't eat is combined with mucus as so-called pseudo-feces and discharged onto the lake bottom where it accumulates. This material, which may benefit bottom feeders, also may reduce the plankton food chain for upper water species.

Status

An invasive nonnative organism. Overland transport on boats, motors, trailers, and aquatic plants poses a great risk for spreading them. Adult zebra mussels can live several days out of water. Boats that have been moored or stored even a day or two in zebra mussel-infested waters may carry hitchhiking mussels attached to their hulls, engine drive units, and anchor chains. Microscopic zebra mussel veligers (larvae) can survive in bilge water, livewells, bait buckets, and engine cooling water systems.

Life Cycle

Female zebra mussels can produce as many as 1 million eggs per year. These develop into microscopic free-swimming larvae (veligers) that quickly begin to form shells. At about three weeks, the sand-grain-sized larvae start to settle; by secreting tough byssal threads, they attach to any firm surface. They clump together and cover just about any surface available. They commonly reach a density of 30,000–40,000 individuals per square meter.

Control

Human Connections

Zebra mussels can clog power plants, industrial, and public drinking water intakes, foul boat hulls, and impact fisheries. Economic impacts of zebra mussels in North America during the next decade are expected to be in the billions of dollars.

Ecosystem Connections

Zebra mussels have a tremendous negative impact on aquatic ecosystems, changing the quality of the water, outcompeting native freshwater mussels, and reducing the plankton available that form the basis for fish life.